- Saving cProfile stats to a csv file

- What is cProfile?

- Saving the stats to a csv file

- Reading the file using Pandas

- Profiling python with cProfile

- Measure

- Profile

- Making sense of the cProfile output

- Reading the cProfile binary output file

- Finding the bottlenecks

- Optimise/Fix ineffient code

- Measure again

- Rinse and repeat

- Summary

Saving cProfile stats to a csv file

As part of testing one of my client code, I used cProfile to profile some code. Though I had never tried profiling code before, I found cProfile easy to use. However, I faced some challenges on how to use the stats which cProfile provided. I looked at ways to use the stats but I didn’t find an option where I can get specific columns from the stats and then use it. I ended up saving the stats to a CSV file and then use pandas to use the stats better. So in this blog, I will give you details on how can you go about doing it.

What is cProfile?

In case you want to get the stats on how your code performs with regards to memory and time, you need to look at some code profilers. This is especially useful in case you want to check what code sections took too long and what functions are getting called how many times. cProfile is one of the standard libraries which Python provides for profiling.

The output of cProfile is a binary file that contains all the stats. Python also provides a pstats.Stats class to print the stats to a python shell. Below is an example of how you can use cProfile to profile a piece of code

""" Script for using cProfile and pstats to get the stats for your code """ import cProfile import pstats, math pr = cProfile.Profile() pr.enable() print(math.sin(1024)) # any function call or code you want to profile. I am using a simple math function pr.disable() pr.dump_stats('restats') p = pstats.Stats('restats') p.sort_stats('time').print_stats() # print the stats after sorting by time

«»» Script for using cProfile and pstats to get the stats for your code «»» import cProfile import pstats, math pr = cProfile.Profile() pr.enable() print(math.sin(1024)) # any function call or code you want to profile. I am using a simple math function pr.disable() pr.dump_stats(‘restats’) p = pstats.Stats(‘restats’) p.sort_stats(‘time’).print_stats() # print the stats after sorting by time

In case I wanted to reuse the stats, I couldn’t find any easy way of achieving it.

Saving the stats to a csv file

I googled a bit and found a useful stackoverflow answer on how to save cProfile results to readable external file. I could use StringIO to stream the result after some data modification and save it to a CSV file.

import cProfile import pstats, math import io import pandas as pd pr = cProfile.Profile() pr.enable() print(math.sin(1024)) pr.disable() result = io.StringIO() pstats.Stats(pr,stream=result).print_stats() result=result.getvalue() # chop the string into a csv-like buffer result='ncalls'+result.split('ncalls')[-1] result='\n'.join([','.join(line.rstrip().split(None,5)) for line in result.split('\n')]) # save it to disk with open('test.csv', 'w+') as f: #f=open(result.rsplit('.')[0]+'.csv','w') f.write(result) f.close()

import cProfile import pstats, math import io import pandas as pd pr = cProfile.Profile() pr.enable() print(math.sin(1024)) pr.disable() result = io.StringIO() pstats.Stats(pr,stream=result).print_stats() result=result.getvalue() # chop the string into a csv-like buffer result=’ncalls’+result.split(‘ncalls’)[-1] result=’\n’.join([‘,’.join(line.rstrip().split(None,5)) for line in result.split(‘\n’)]) # save it to disk with open(‘test.csv’, ‘w+’) as f: #f=open(result.rsplit(‘.’)[0]+’.csv’,’w’) f.write(result) f.close()

Reading the file using Pandas

Now I could simply use pandas dataframe to get the specific stats I need and then reuse it in my code

df = pd.read_csv("test.csv") req_column = df.ncalls # gets only the column related to the number of times methods are called print (req_column)

df = pd.read_csv(«test.csv») req_column = df.ncalls # gets only the column related to the number of times methods are called print (req_column)

Hope you find this article useful. Happy testing and enjoy profiling python code!

I am a dedicated quality assurance professional with a true passion for ensuring product quality and driving efficient testing processes. Throughout my career, I have gained extensive expertise in various testing domains, showcasing my versatility in testing diverse applications such as CRM, Web, Mobile, Database, and Machine Learning-based applications. What sets me apart is my ability to develop robust test scripts, ensure comprehensive test coverage, and efficiently report defects. With experience in managing teams and leading testing-related activities, I foster collaboration and drive efficiency within projects. Proficient in tools like Selenium, Appium, Mechanize, Requests, Postman, Runscope, Gatling, Locust, Jenkins, CircleCI, Docker, and Grafana, I stay up-to-date with the latest advancements in the field to deliver exceptional software products. Outside of work, I find joy and inspiration in sports, maintaining a balanced lifestyle.

Profiling python with cProfile

A couple of days ago, I had an assignment for an Information Retrieval class that basically involved:

- Indexing a large corpus (Reuters from nltk )

- Searching it using boolean queries (eg. bill AND gates )

For the second part of the of the assignment, performance was pretty important. Since we would want to return results for the user’s queries quickly.

This blogpost is basically about how I used python’s cProfile to identify and fix bottlenecks/slow parts in my code. Most of these bottlenecks would have been hard to identify without the profiler.

During my internship at Quora, one of the things I worked on was POST speed improvements for core actions across the product. It was my first brush with speed work and the main lesson I took away was the importance of measuring and profiling before attempting to optimise.

«Bottlenecks occur ins surprising places, so don’t try to second guess and put in a speed hack until you have proven that’s where the bottleneck is.» — Rob Pike

Measure

After getting a working submission out. I proceeded to measure/benchmark my code. Since this program was meant to run as a script from the command line, I used the simple time command-line tool to roughly benchmark how fast my code was.

$ time python search.py # real 0m1.521s # user 0m1.250s # sys 0m0.142sProfile

Once I was happy with the measurement, I proceeded to profile my code using cProfile .

$ python -m cProfile -o profile_output search.pyThe -o flag basically specifies an output filename for cProfile to write its output to. (Without which, it’ll simply spit out the stats to the stdout, which is undesirable since we’d be unable to sort/drill down into specific functions.)

Making sense of the cProfile output

The cProfile output is a basically binary file that contains the following information:

(For each function called in the python program)

- How long each call took (percall, inclusive and exclusive)

- How many times it was called (ncalls)

- How long it took (cumtime: includes the times of other functions it calls)

- How long it actually took (tottime: excludes the times of other functions)

- What functions it called (callers)

- What functions called it (callees)

If you didn’t specify the output, you’ll basically only get a dump of the information without the caller/callees part. (Which is quite helpful in making sense of everything). You’d also lose the ability to dynamically re-sort the information based on your preferred metric (unless you re-profile it with a -s flag (I think)).

Reading the cProfile binary output file

In order to read this binary file, python provides a pstats.Stats class that happily spits out the various infomation for you in a python shell (when called with the relevant methods).

I found this rather tedious and googling around for an easier way to read this binary file yield nothing. I just wanted a simple way to:

- See all the information

- Sort them with a single click

- Drill down to functions (and their callers and callees) with a single click

(These as oppose to manually calling methods on the Stats object each time.)

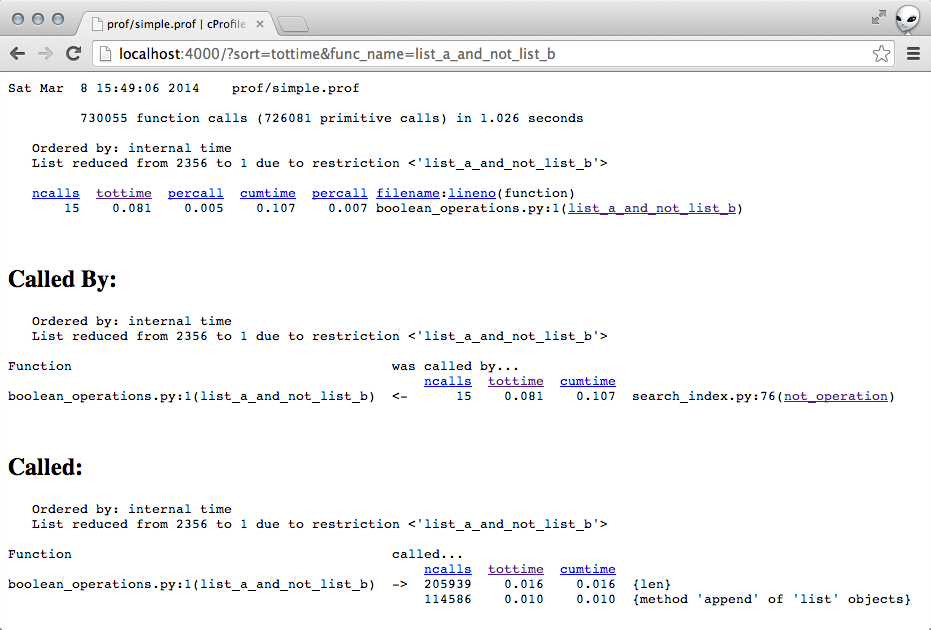

So I wrote this: CProfileV. Which is bacially a thin wrapper for viewing python cProfile output in your browser. Yay!

[UPDATE]: cProfileV has been updated. See https://github.com/ymichael/cprofilev for the latest usage instructions.

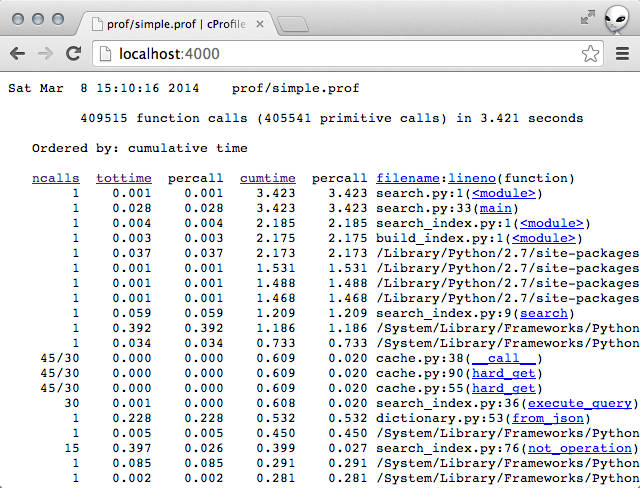

# Install cprofilev $ sudo pip install cprofilev # Call it with your cprofile output $ cprofilev -f /path/to/cprofile/output # Navigate to http://localhost:4000Finding the bottlenecks

The pstats.Stats object allows you to sort by the various keys and their combinations. Most often, I find that the most useful sort keys are:

- cumulative time

- total time

- calls (to find unneccessary function calls (objects being created in a loop for instance))

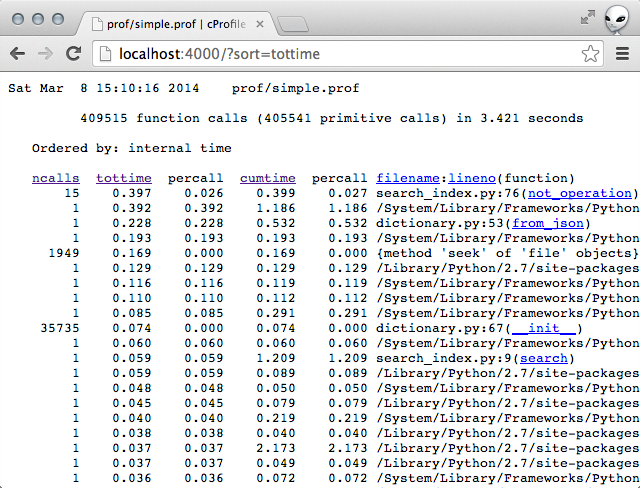

Sorting by total time for me yielded this:

The top line stood out to me. The function not_operation was taking a suspiciously long time.

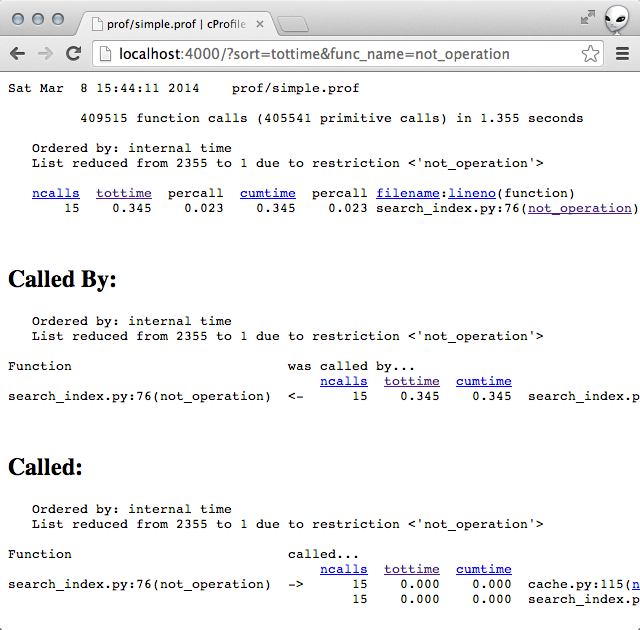

Clicking into the not_operation showed that the functions it was calling were not taking a lot of time. (Implying that the slowness was due to some code within the function itself.)

# line 76 of search_index.py def not_operation(operand, dictionary, pfile): """Performs the operation `NOT operand`.""" # A list of all the documents (sorted) all_docs = dictionary.all_docs() # A list of the documents matching `operand` (sorted) results = get_results(operand, dictionary, pfile, force_list=True) return [doc for doc in all_docs if doc not in results]So it turns out that the list comprehension in the function was basically really inefficient. It became super obvious once I narrowed down that not_operation was slow.

Optimise/Fix ineffient code

Excited to have found a possible bottleneck, I quickly implemented a fix.

# the fix. def not_operation(operand, dictionary, pfile): """Performs the operation `NOT operand`.""" # A list of all the documents (sorted) all_docs = dictionary.all_docs() # A list of the documents matching `operand` (sorted) results = get_results(operand, dictionary, pfile, force_list=True) return list_a_and_not_list_b(all_docs, results) def list_a_and_not_list_b(a, b): """Returns `a AND NOT b`. Both a and b are expected to be sorted lists. """ results = [] idx_a = 0 idx_b = 0 while idx_a < len(a) and idx_b < len(b): if a[idx_a] < b[idx_b]: results.append(a[idx_a]) idx_a += 1 elif b[idx_b] < a[idx_a]: idx_b += 1 else: idx_a += 1 idx_b += 1 while idx_a < len(a): results.append(a[idx_a]) idx_a += 1 return resultsMeasure again

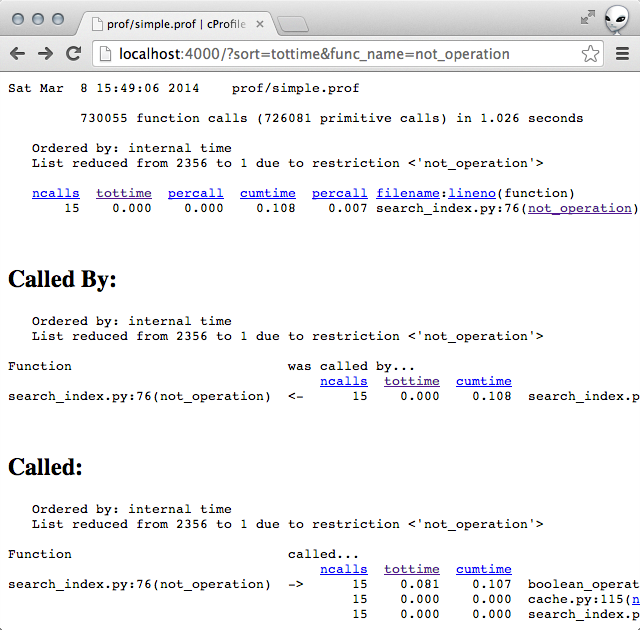

Measuring the time taken showed promising results. With this fix, the time taken dropped from roughly 1.5s to 1.15s.

time python search.py # real 0m1.160s # user 0m1.018s # sys 0m0.133sProfiling the code showed that the slowness was no longer coming from not_operation .

Rinse and repeat

This time though, the most of the time seemed to be spent in the list_a_and_not_list_b operation.

In particular, I seemed to be doing ~200k len operations and ~115 append operations on some list objects.

This seemed like a red-flag so I took a closer look at the list_a_and_not_list_b function.

It turns out that I really didn't need the while loop at the end of the function.

# From this. while idx_a len(a): results.append(a[idx_a]) idx_a += 1 # To this. results.extend(a[idx_a:])Measuring with this new change:

time python search.py # real 0m0.895s # user 0m0.771s # sys 0m0.122sWoot! Got it to run under a second!

Summary

Overall, I'm pretty happy with the performance gain I got. I did a couple more that I didn't cover here (some other boolean operations were performing poorly under other testcases). Its a pretty cool feeling to methodically find bottlenecks and fix them.